On June 12, the nation commemorates the 127th anniversary of Philippine Independence—a historic milestone that marks the end of colonial rule and the beginning of self-governance. Yet, more than a century later, the question remains pressing: Are we truly independent, or are we still dependent on systems, narratives, and structures that hinder genuine freedom and national dignity?

Independence is not merely about sovereignty on paper. It is about the people’s capacity to shape their future through informed choices, social justice, and responsible leadership. As we reflect on our journey as a nation, it is important to examine the deeper dimensions of freedom—especially in the context of contemporary social, political, and moral challenges.

The Right to Expression: Protected, But Not Always Heard

The 1987 Philippine Constitution, Article III, Section 4, guarantees that:

“No law shall be passed abridging the freedom of speech, of expression, or of the press…”

However, this right exists more in theory than in practice for many Filipinos. While expression is legally protected, many citizens—especially those in vulnerable sectors—report being unheard, dismissed, or even punished for speaking out. Numerous accounts during the War on Drugs campaign saw the poor being silenced not by law, but by fear. The chilling effect on civil society has led many to withdraw from public discourse, wary of reprisal or discredit.

Ordinary citizens, including activists, farmers, students, and workers, have reported being arrested without warrants, imprisoned without due process, or red-tagged without credible basis. These cases call into question whether the rights enshrined in the Constitution are truly accessible to all.

Education and Media: Tools of Enlightenment or Manipulation?

Education is the cornerstone of democratic participation. According to Article XIV, Section 3(2) of the Constitution:

“All educational institutions shall inculcate patriotism and nationalism, foster love of humanity, respect for human rights…”

Yet systemic issues in the Philippine education system—from underfunded public schools to politicized curricula—impede the development of critical thinking among students. In remote islands and impoverished communities, young Filipinos often receive insufficient instruction on civic responsibilities, national history, and constitutional rights. In this context, education does not empower but risks perpetuating cycles of dependence and misinformation.

The media, too, plays a significant role. While a free press is a pillar of democracy, the spread of fake news, sensationalism, and biased reporting has deeply influenced public opinion. Some media channels have been accused of prioritizing entertainment over facts, contributing to a political culture that rewards popularity rather than competence. The rise of social media “loyalists” and misinformation networks has further blurred the line between truth and propaganda.

Leadership and Political Manipulation: Justice for Whom?

Democracy depends on leaders who uphold integrity and accountability. Yet many citizens have come to question whether the country’s democratic institutions serve the people or protect political interests. The impeachment process, for example, which is designed to check abuses of power, has at times been delayed or derailed by partisan interests. Instead of acting as impartial arbiters, some members of the Senate and House of Representatives are seen taking sides or behaving more like defense attorneys than custodians of the Constitution.

The No Contact Apprehension Program (NCAP) and other state initiatives reflect both the potential and pitfalls of governance. While designed for efficiency and public order, such programs have been criticized for lack of transparency, unclear implementation, and disproportionate impacts on the poor.

Meanwhile, the case of San Miguel Corporation in Bugsuk, Palawan, where residents and fisherfolk have faced eviction or criminal charges in the name of development, raises concerns about corporate influence over local communities. These incidents challenge the equitable enforcement of RA 8371 (Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act) and RA 6657 (Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law), laws that are supposed to protect indigenous land and rural livelihoods.

In contrast, many politically influential figures are often spared from scrutiny or penalty, reinforcing perceptions of selective justice.

The Common People: Burdened by Poverty, Denied of Justice

Despite being the proclaimed focus of many social programs, the common Filipino continues to suffer from systemic neglect. Aid distribution, or ayuda, has at times been tied to political allegiance. In several barangays, promises of relief are used not simply to support communities but to shape political loyalties. This practice not only undermines democracy but treats poverty as a tool for manipulation rather than a condition to be solved.

Worse, individuals in rural communities have been arrested for minor offenses or land-related disputes, while large-scale corruption and political impunity persist in higher offices. Such disparity not only weakens trust in public institutions but also erodes the moral fabric of the nation.

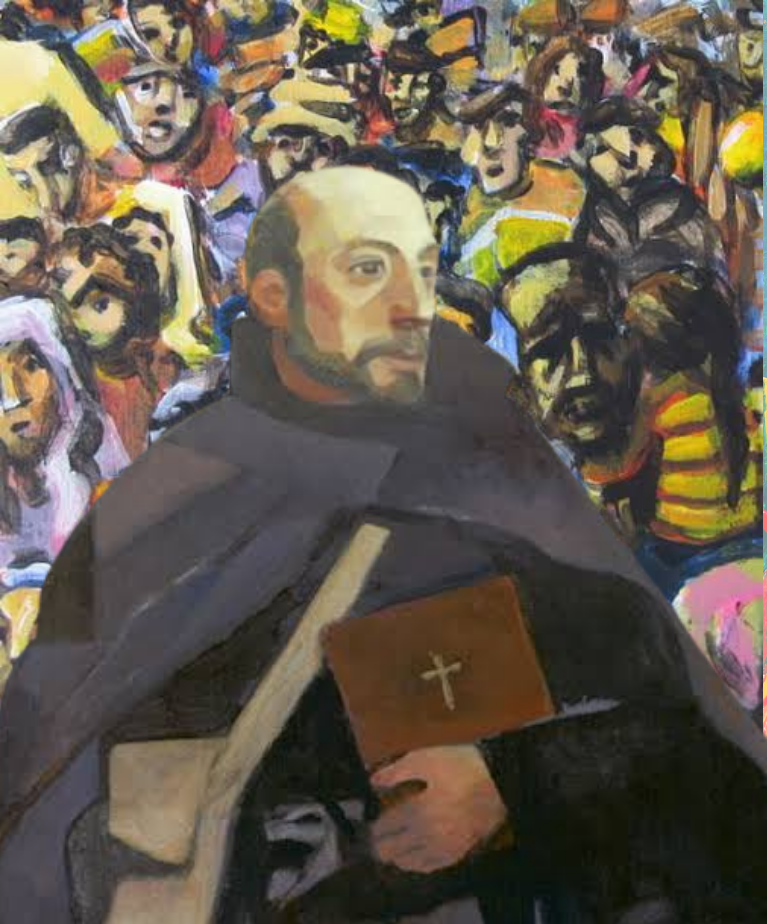

Faith and Social Doctrine: A Moral Reflection

The Catholic Church has long advocated for justice, participation, and the dignity of every person. In Centesimus Annus (1991), Pope St. John Paul II reminds us:

“A democracy without values easily turns into open or thinly disguised totalitarianism.” (CA, 46)

Pope Francis, in Fratelli Tutti (2020), observes:

“Politics must not be subject to the economy, nor should the economy be subject to the dictates of an efficiency-driven paradigm of technocracy.” (FT, 177)

The Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church affirms:

“Participation is a duty to be fulfilled consciously by all, with responsibility and with a view to the common good.” (CSDC, 189)

These teachings challenge all sectors—government, civil society, and faith communities—to foster a culture where truth, equity, and human dignity prevail over convenience, control, and silence.

Conclusion: The Ongoing Struggle for Meaningful Freedom

The 127th anniversary of Philippine Independence is more than a historical marker; it is a moment for national introspection. Are we truly free, or are we dependent on personalities, structures, and narratives that limit our growth as a people?

True independence is not only about external sovereignty. It is about internal liberation: from poverty, misinformation, political dependence, and moral indifference. It involves recognizing the dignity of every citizen, defending the rule of law, and actively participating in the democratic process with both courage and conscience.

Let this year’s commemoration serve not just as a celebration, but as a challenge—to reclaim the freedom envisioned by our heroes and to ensure it lives in every Filipino today.

References:

- 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines

- Republic Act 8371 – Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act

- Republic Act 6657 – Comprehensive Agrarian Reform Law

- Centesimus Annus, Pope St. John Paul II (1991)

- Fratelli Tutti, Pope Francis (2020)

- Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church (Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace, 2004)

About the Author

Leonard “Leo” Francisco is currently the Assistant Content Creator for the website and social media pages of the Society of Jesus’ Social Apostolate, under the leadership of Fr. Emmanuel Alfonso, SJ. He is a seminarian under regency while pursuing theological and masteral studies at the Loyola School of Theology, Ateneo de Manila University.